OP 4 - GENOA INNER HARBOR INSTALLATIONS AND SHIPPING

The operation against enemy installations at Genoa harbor began on the night of August 13/14, 1944. The reason for this attack became obvious and public knowledge on the 15th of August, 1944. This operation was in support of "Operation Dragoon" - the allied invasion of Southern France. D-Day for Operation Dragoon was August 15th, 1944. Allied ships off the coast of Naples, Italy preparing for the invasion of Southern France on August 7, 1944.

Allied ships off the coast of Naples, Italy

preparing for the invasion

of Southern France on August 7, 1944.

As early as August 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) had explored the possibility of a diversionary attack in southern France to be launched in coordination with Operation Overlord, the main cross-channel assault at Normandy. Mounting a new invasion, however, would require troops from Italy, and the intensified fighting there, especially at Anzio and along the Gustav Line, consumed more troops, shipping, and supplies than the Chiefs had anticipated, forcing them to postpone a decision on any peripheral invasions until after the fall of Rome.

Following the liberation of Rome, the plan to invade southern France won approval. Eisenhower needed ports to support his forces pouring into Normandy, and Marseilles, on the French Riviera, fit the bill. An invasion there promised a direct route to vital German industry in the Ruhr region. Thus, on July 2, the CCS set a target invasion date of August 15.

As invasion planning proceeded, MAAF's fighters and bombers in Italy continued supporting the Fifth and Eighth Armies drives toward the Po River, appearing only infrequently over southern France. Bombers, however, flew several important pre-invasion missions. On July 5, 228 B-17s and 319 B-24s hit marshaling yards at Montpellier and Bezier and the naval installations at Toulon. They quickly staged several more raids against bridges and airfields. In early August, more than one thousand bombers attacked rail lines and oil storage installations in the invasion area. By August 5, the remainder of the MAAF joined the assault. Fighter-bombers hit bridges, locomotives, rolling stock, and railroad tracks in and around Marseilles. B-25 medium bombers struck important bridges at Avignon. Five days later, a preparatory bombing campaign began in earnest. Allied aircraft attacked coastal defense guns and radar stations in the assault area, then spread out to strafe Luftwaffe aerodromes as distant as northern Italy. Day by day, as the air attacks intensified, troops, shipping, and troop carrier aircraft assembled. At the end of the remarkably short span of six weeks, the landing force stood ready.

In the early morning hours of August 15,396 planes of the Provision al Troop Carrier Air Division dropped more than five thousand American and British paratroopers near Le Muy, France. A few hours later, the MAAF reinforced this initial wave with glider-borne units. By dawn, the paratroopers were fighting for Le Muy, while heavy and medium bombers and fighter-bombers swept over the invasion area and destroyed underwater obstacles, beach defenses, and coastal guns. The payoff came as the American Seventh Army and the French II Corps hit the beaches against light and disorganized enemy resistance.

|

US troops of the 7th Army in their landing craft approach the beaches of Southern France on the morning of August 15, 1944. |

Aided and protected by MAAF's aircraft, the assault troops quickly consolidated their positions and moved inland. By the end of D-Day, the U.S. 45th Division reached Le Muy and linked up with airborne troopers dropped the previous night. French and American units on the invasion's left flank, aided by medium bombers, turned west and captured Toulon and Marseilles at month's end.

Concurrently, the main American force, preceded by medium and fighter-bomber attacks, moved up the Rhone Valley as German traffic streamed north to escape the Allied juggernaut. Unprotected by the Luftwaffe, the retreating Germans were easy targets. Allied aircraft bombed and strafed the congested columns at will during daylight, shredding the fleeing troops and transport. Later, the American Seventh Army reported more than two thousand destroyed vehicles choking one stretch of territory. Periodically, the Germans turned and fought, but Allied ground and air forces quickly overwhelmed them.

Finally, on September 6, near the Belfort Gap, the Germans stood their ground long enough to permit an orderly withdrawal. Shortly thereafter, the Seventh Army and the French II Corps met elements of Patton's Third Army, fresh from its Normandy breakout and dash across France. Together, the two armies turned toward the Rhine and the attack on the German homeland.

The invasion of southern France was the last of a series of amphibious operations in the Mediterranean that began in North Africa and continued with assaults on Pantelleria, Sicily, southern Italy, and Anzio. None was more successful than that in the south of France. The battle-won lessons of the earlier invasions finally bore fruit on the beaches of the French Riviera and in the campaign that followed.

Conventional Allied amphibious assaults, involving thousands of men fighting along a clearly defined battlefront, were vital to victory. But European rebellion against Axis occupation, although unconventional and peripheral, was also important in defeating Hitler. Here, too, 205 Group made a major contribution.

US Troops offload vehicles from

landing craft on the

beaches of St.Tropez on August 15, 1944.

At the 37 Squadron briefing for the nights mission, 205 Group RAF Captain P. R. Beare, DSO, DFC, announced the coming invasion of Southern France. He did so to stop the "busy speculation" which had been going on for some time. All were warned not to talk about the invasion until the official announcement had been made. The inner harbor at Genoa contained a number of enemy vessels, motor torpedo boats and other light naval craft. Installations included docks, shipyards, and a number of heavy gun emplacements. All were targeted on this nights mission. Eleven aircraft from 37 Squadron were detailed and operated.

MacIsaac & crew took off from Tortotella at 1940 hours in Wellington Mk.X number LN798 - "D". This aircraft was to become their normal assignment for some time. On this night they carried nine 500 pound bombs and a load of "nickels" - propaganda leaflets. Flight time to Genoa was about four hours. The crew observed part of the invasion fleet on their outbound leg of the operation.

Flak over the target was heavy and accurate. Due to the intense flak it is not surprising that no night fighters were encountered. The weather was good and the TI’s were well placed . Eleven aircraft dropped a total of ninety seven 500 pound bombs at 2330 to 2239 hours from an altitude of 7900 to 8700 feet. Fifty five packets of "nickels" were also dropped. All crews identified the target, bombing was well concentrated, and the attack appears to have been very successful.

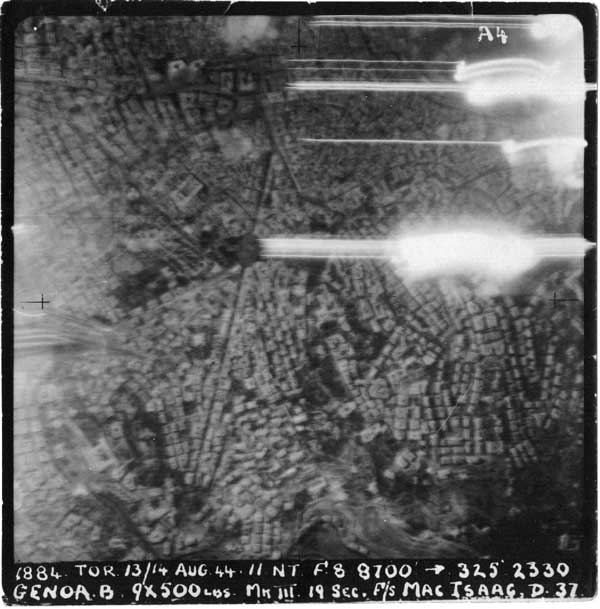

F/Sgt MacIsaacs aiming point photograph over Genoa on the night of August 13/14 of 1944. Flak batteries are clearly visible. MacIsaac dropped his bombs at 2330 hours on a heading of 325 degress from 8700 feet. His "stick" of bombs was observed to burst "spot on" across the red TI’s. |

One aircraft, Wellington Mk.X MF347 flown by Sgt. H. E. Daynes RAF, was lost on the return leg of the operation.

Over Genoa, Sgt. Daynes had two 500 pound bombs hang up in the bomb cell. This situation was complicated by engine trouble, which caused excessive fuel consumption en route to Tortorella. The captain decided to bale out due to shortage of fuel and the danger of attempting a forced landing on an airfield with two bombs on board. The entire crew baled out safely over the Rome area.

MacIsaac, due to shortage of fuel and congestion over Tortorella, made a safe emergency landing at the Celone airfield at 0109 hours.