LIVING CONDITIONS

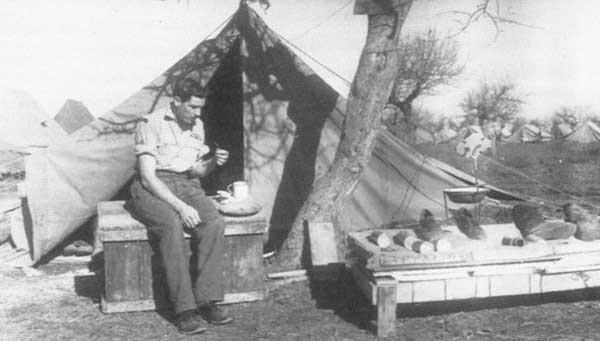

An RAAF pilot finishes his lunch while airing out his homemade bed at Tortorella.

Accommodations for some RAF squadrons of 205 Group were better than others, but it was all sub-standard.

George Carrod of 142 Squadron wrote:

"...compared with the USAAF, life was pretty grim; we had a small ridge tent for the five of us to sleep in, you either slept on the floor or you made your own bed. I managed to find two planks of wood which I balanced on two empty ammo boxes using my parachute as a pillow. I later managed to find a stretcher from a blown up Red Cross vehicle. We had no toilets, facilities for washing were non-existant and most of us went down with dysentery or jaundice but morale was very high. I do not think that, had we had to bale out, our ‘chutes would have opened as they were never checked or repacked. In fact one pilot refused to fly for that reason and was promptly court-martialled for Lack of Moral Fibre (LMF). "

Don Twigg of 70 Squadron recalls:

"At Tortorella, 37 Squadron were camped in an olive grove and we (70 Squadron) camped in a nearby wheatfield. The Italian olive pickers started work at dawn singing operatic arias which were not appropriate after flying all night. The only way to shut them up was to discharge a .38 into the trees... "

Dennis Hurd of 104 Squadron:

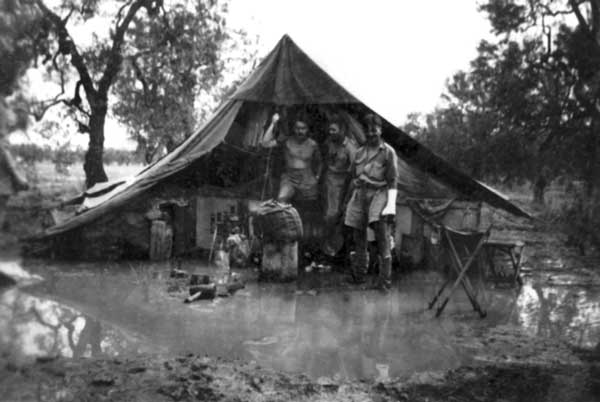

"Sudden summer thunder storms were not uncommon and on one occasion every tent was flooded. This was unfortunate because in some cases crew had dug out the ground beneath the tent to give extra headroom. They suffered soaked possessions more than others."

Aircrew in a flooded tent among the olive groves

at Tortorella.

Food stands as an equal with housing in any military morale context and at the Foggia airfields that was generally sub-standard too. Ieuan Jones of 150 Squadron summed it up well:

"The diet was adequate but boring. The food was prepared in a Field Kitchen (oil/sand and metal grill) and there was much reliance on fried corned beef and Spam, supplemented by private venture eggs (swapped with the locals for cigarettes). The cooks had an inexhaustible supply of tea - dark brown, well-stewed with condensed milk. Thus, after night flying, breakfast was always available. "

Tom Fannon of 37 Squadron explained some improvements:

"The food was mostly from dehydrated concoctions of potatoes, onions and even meat. Later on, unofficially, we made a deal with one of the nearby American Messes. We exchanged our ‘hard liquor’ ration for US delicacies such as tinned chicken, ham and a twice daily offering of doughnuts - a change much appreciated. "

George Dalgliesh, Air Gunner with 178 Squadron has similar memories:

"Occasionally we were invited over to 98 Bomb Group’s parachute silk festooned mess in which we indulged in ice cream, real fruit juice and table tennis. Their hospitality was tremendous. They also arranged for Joe Louis to include us in his exhibition tour. "

Tom Parker of 104 Squadron on conditions at the Foggia airbases:

"Frequently we would return from ops to find our tents flooded and personal belongings awash or lost. Sandfly fever and dysentery added to the general discomfort. "

Surprisingly, in the face of all these adverse conditions and the hostile environment, moral is generally remembered as very high. Tom Fannon of 37 Squadron illustrated the importance of leadership in maintaining high moral which:

"...was a little down as we joined the Squadron, but on the arrival of a new wing Commander, Henry Langton (later to be Sir Henry Calley) this rose rapidly. A local farmhouse (of the Mussolini Regime) was taken over for a Mess bar and a heated room for our flying clothing. I remember asking if we could organize a football team to play the other Squadrons - next thing I knew I was on my way to Naples to collect all the equipment possible. "

"And - not the least of the reasons for good feeling, in fact a real reason, was the work of our Padre, Rev A.B. Jestice. Off the record he must have flown on many ‘ops’, as quite often he would say, "put a ‘chute in for me tonight". He was responsible for a lot of the improvements - so much so that I know that his care and understanding resulted in one of our wireless operators receiving the DFM [Distinguished Flying Medal]. He did this, ran Musical Appreciation evenings and organized electricity for our tents. "

RAF tents pitched among the olive trees at Amendola - 1944.

RAF Pilot Maurice Lihou arrived on No. 37 Squadron in March of 1944 - he describes, in wonderful detail, conditions and everyday life at Tortorella:

"A battered and dilapidated old farmhouse, set in a field of mud, was the headquarters of 37 Squadron. From there on we [Lihou and his four crew members] were taken to the tents that had been erected in the nearby olive grove. However, because Riggy [Navigator, RCAF] was an officer, he had to go to a section of the grove reserved for the officers quarters. Riggy was quite annoyed with this form of segregation, but was much happier when he realized how cramped up we would have been in the one tent.

The farmhouse at Tortorella"The tents were the bivouac type, about twelve feet long and six feet wide and four and a half feet high. In order to obtain more headroom, the first job was to dig out a hole of about eighteen inches under the tent itself, being careful to insure that the walls of the hole we had dug did not collapse into it. It was very difficult work, particularly as the roots of the olive trees had to be cut away as we came across them. The floor was covered with a rubber groundsheet, supplied with the tent.

"There were no beds or palliasses, everyone had to find what material they could to construct their own beds or sleep on the ground. I was able to scrounge four very strong round cardboard containers with metal bottoms that the tail fins of the bombs came in. Putting these in my bed space, which was in the front half of the tent, I placed one in each corner with the metal bottoms uppermost. Each was about a foot across, and this gave a strong base upon which to place an old Venetian blind that I had previously found lying around on a scrap heap. The result was a bench, off the ground, on which to lie. Finally, I used my kapok-lined inner flying suit to act as a mattress and with the two army blankets that were issued to me, plus my RAF greatcoat over the top of them, that became my bed.

"My pillow was my kitbag, rolled up, in which I also stored my spare clothing – primitive, to say the least, particularly as the bed had to be far enough away from the sides of the hole to prevent grass snakes and other unwanted creatures from getting into it, spiders and beetles being the chief offenders. The tops of the beds came level with the ground outside, and if they were placed too near the sides it was a simple matter for these creatures to slip in under the canvas and into the bed! It wasn’t a happy thought, knowing that you could wake up with something like that crawling over you. Each night before I turned in I had to shake the so-called bed clothes to remove these unwanted visitors.

"Len [Bomb Aimer, RCAF] slept opposite me. He had managed to find an old door which he placed on ammunition boxes and made his bed on that. There was a gap of about two feet between us. Sparks [Wireless Operator, RAF] and Jock [Air Gunner, RAF] had similar positions behind us at the rear of the tent. They had made their beds by making wooden and metal frames with strong twine laced crisscross fashion over them. These were also propped up on tail-fin containers and old wooden ammunition boxes to keep them off the ground.

"Having gotten ourselves reasonably comfortable, the next job was to dig a small ditch around the outside of the tent so that rain dripping off the sides would be carried away and not seep into the interior. Finally, sacks and cardboard were placed outside of the front of the tent in an effort to stop the mud being carried off our feet into the inside - not easy to prevent when it was pouring with rain. Lighting was provided by shaded candles or homemade oil lamps, but because of the blackout were very rarely used.

"Heating came from a drip stove which we made ourselves. A small jerrycan formed the base plate of the stove, upon which dripped used oil, taken from the sumps of the aircraft engines. The oil dripped from a small oil drum, located outside the front end of tent, through a narrow metal pipe controlled by a little tap, onto the metal base plate. Next to this, water from another similar sized drum, also housed outside and also controlled by a small tap, dripped alongside that of the oil. To initiate the process, a small fire was lit under the base plate. As soon as it became hot, the oil and water taps were turned on, allowing small quantities to drip on the top of the stove. The heat ignited the oil and the dripping water caused it to splash over the surface of the base plate, causing the whole of the base plate to become red hot.

"After the fire had gone out from under the base plate, the heat from the top of the stove continued to ignite the oil. We also used this heat to boil water for strip bathing, shaving, making cocoa, and to cook what food we could buy when the food from the field kitchen became unbearable. There were several snags to this arrangement: the risk of fire should the flap of the tent get too near it; and the care needed when stepping in and out of the tent barefoot or in socks, particularly at night. But the most unpleasant snag was when a large black beetle landed on top of the stove. It frizzled and, as it burnt, it caused such a stench that evacuation of the tent became the number one priority. These beetles would be attracted by the glow of the stove, and before they could be chased away, would commit Hari Kari by doing three point landings on top of the hot plate!

A 178 Squadron ground staff shack at Amendola.

The oil-fired heating is prominent in the background."The other piece of essential equipment was the jerrycan in which to hold our drinking water. This water was also used for such things as cooking, washing - both our bodies and our clothes - and as a fire extinguisher in case the tent caught fire. Water came into the camp in a bowser which was used to serve the whole camp, and each member of the crew took it in turns, whenever the jerrycan became empty, to go and collect the water. This was a chore most looked forward to because, whilst in the queue that gathered there, we were able to meet and chat with the other crew members. It was here that most of the rumors started, particularly early the next morning after a previous nights raid.

‘I hear we lost so many last night.’

‘So and so didn’t come back.’

‘The Yanks are going back today to finish it off.’

‘I hear it’s such and such a place tonight.’"And so on. At the back of the bowser there was a big heavy tap that was used to fill the jerrycans. Below it the ground was like a quagmire, where the water, during the filling of the cans, had overflowed. When it was cold our feet became frozen stiff through standing around in our gumboots, which we wore instead of our flying boots to protect these from getting wet and muddy. If some idiot stamped his feet in an effort to warm them he was greeted with shouts of derision as the mud splattered everywhere.

"Carrying the heavy jerrycan filled with water back to the tent was no easy matter either, and quite often another member of the crew would turn up to give us a hand. The water tasted foul, being heavily chlorinated, therefore once back in the tent a further can was used in which to boil it and, when cool, each member filled his water bottle up with the stuff. Nevertheless, sometimes when we were not on duty, an evening in the tent together could be quite cozy. The stove gave off a comfortable heat and, sitting on the beds of myself and Len, with a blanket wrapped around our shoulders, the crew would brew up a mug of cocoa, make toast and bacon and eggs, light up a fag and have a chat. Often we would save our candle ration by not lighting them and just sit around the warm red glow of the stove, telling stories of our lives in civvy street. Other times, after we had received our beer and chocolate rations we would sit around the stove again in the dark, having a quiet drink and listening to the steady drip of the stove and the hiss of the water as it splashed across the hot plate, turning it to steam.

"It was normal practice for the crews who were selected for ops [‘operations’ is the RAF terminology for a combat mission] that night to have their names posted on the operations board in the morning. They would be on standby, carrying out the usual routine equipment checks, air tests and attending briefings until the operation was either confirmed or scrubbed. If scrubbed, it was then a rush to the Mess for a jolly good drink and singsong.

"The Mess and its bar was a homemade affair. The building was a Nissen hut, with the bar at one end. Tables and chairs were made from bomb carton cases. The large ‘cookie’ bomb case was cut down to serve as a table, and the smaller bomb cartons were cut out in the shape of a chair [RAF aircrew referred to the massive British 4000 lb bombs as ‘cookies’]. The atmosphere was laden with smoke, and the mood reflected the emotions of the airmen: celebrations when an op was cancelled; sadness when crews never returned; and celebrations when crews were ‘tour expired’. I kept away from the place when losses were high and, more particularly later, when the ‘tour expired’ celebrations seemed to be getting less and less frequent.

"The Australians on the squadron were a wild bunch. It was not uncommon , after a rowdy drinking session, for them to pile the bomb cartons in the center of the floor and set them on fire. On other occasions they would play ‘Cowboys and Indians’, whooping around the tents with their revolvers and firing them using live ammunition. There were several tents with unexplained bullet holes in them! Or they would take a gharry and go pig sticking around the Italian farms. On one occasion they even upended the Squadron Commanders caravan with him in it. For that the Mess was put out of bounds for two weeks.

"After about a month or two of this sort of camp life, nights like that seemed to me like a bad dream. It was all so unreal. Connie [Lihou’s wife] and home seemed so far away. I became fed up and wanted to get away, as far as possible from that bloody camp and all it stood for. It was nothing but mud and slime. The food was gut rot. Even after boiling, the water was foul and still tasted of chlorine. No wonder you got ‘the shits’.

"The lavatories consisted of a tent, with a trench dug in the ground, and a plank with holes cut in it for you and about a half dozen other men to sit on. Underneath each hole were large buckets. We had to use what paper we could find. Sometimes some wag would set fire to the paper in the bucket. The stench was horrible. If you had what was known as ‘eyetie tummy’ and had to use them under those circumstances, you wanted to be sick.

"I felt trapped in the ugliness of the camp. Its barren trees, its bombed out buildings, its greyness, its rows of dull canvas tents, its bugs, its dirt, its monotony.

RAF Pilot Maurice "Lee" Lihou outside his tent during the winter of 1944-45."Sadly, we lacked other friends. The crew ate, slept, worked and fought together. We went off camp together, we drank together, we went to the pictures together and to the showers together. As much as we got on well together, there were times when I cried out for something different. I was also trapped in our dependence upon each other. Living under canvas in primitive conditions was, to say the least, extremely restrictive, besides being very frustrating and emotionally draining if we should carelessly let our thoughts slip back to home life.

"Night-time bombing operations brought their own pressures without the added pressures of a sordid lifestyle. When we came back from an op we got fed up with ‘trying to make the best of it’. We would have given anything for an easy chair or a comfortable bed or even a decent meal. The main problem wasn’t really the difficulty of making friends, but that everyone on flying duties held back. We didn’t want to become too involved with other crews because of the fear that you might not see them again.

"And so the daily routine and squalor dragged on and on: eat, sleep, drink and ops."